It's funny to see just how much this blog has changed in the 6+ years I've been writing it... for instance, for the first couple of years, it was exclusively book reviews of the fiction I was reading, but now, I haven't posted an individual, in-depth review of a "made-up" book since last year!

To be perfectly honest, there's no book I would rather have as my first serious take on critical fiction reading for 2017, especially because this socially-aware science fiction literary hit seems a little uncomfortably prescient for the coming years.

And fair warning: it's a bit of a long one.

I was taken as soon as I saw the cheerful signage on display near the "Recent Releases" caddy in the YA section of my local library. "... Do you believe in love at first line?"

To be fair, I'm crazy about these kinds of challenges, in general. They rarely go my way - both my "Blind Date with a Book" choices so far have ended up being DNFs - but the sheer novelty of being forced to step out of your comfort zone is too enticing of a challenge to ignore.

I chose this sentence because it seemed whimsical enough: "We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck." Unfortunately, as soon as I opened the newspaper wrapping, my heart sunk.

I chose this sentence because it seemed whimsical enough: "We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck." Unfortunately, as soon as I opened the newspaper wrapping, my heart sunk.

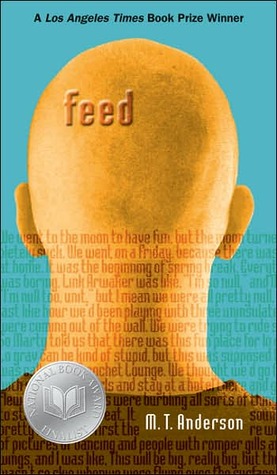

M.T. Anderson's Feed. I had never heard of it before, but it had won a National Book Award. The cover seemed very 2000s, with bright orange-and-teal coloring and an off-putting bald head, superimposed with lines of text in a cheesy font. I considered simply sticking the book back in my library bag to return on my next excursion... but then again, Mama didn't raise no quitter. I knew I had to give the book its chance.

To be perfectly honest, there's no book I would rather have as my first serious take on critical fiction reading for 2017, especially because this socially-aware science fiction literary hit seems a little uncomfortably prescient for the coming years.

And fair warning: it's a bit of a long one.

I was taken as soon as I saw the cheerful signage on display near the "Recent Releases" caddy in the YA section of my local library. "... Do you believe in love at first line?"

To be fair, I'm crazy about these kinds of challenges, in general. They rarely go my way - both my "Blind Date with a Book" choices so far have ended up being DNFs - but the sheer novelty of being forced to step out of your comfort zone is too enticing of a challenge to ignore.

I chose this sentence because it seemed whimsical enough: "We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck." Unfortunately, as soon as I opened the newspaper wrapping, my heart sunk.

I chose this sentence because it seemed whimsical enough: "We went to the moon to have fun, but the moon turned out to completely suck." Unfortunately, as soon as I opened the newspaper wrapping, my heart sunk.M.T. Anderson's Feed. I had never heard of it before, but it had won a National Book Award. The cover seemed very 2000s, with bright orange-and-teal coloring and an off-putting bald head, superimposed with lines of text in a cheesy font. I considered simply sticking the book back in my library bag to return on my next excursion... but then again, Mama didn't raise no quitter. I knew I had to give the book its chance.

Unfortunately, it wasn't an easy go, at first. The book starts off so Jetsons-type science fiction that it completely threw me off. I mean, they go to the moon on vacation, and take part in zero-gravity dance parties. They have hover-cars and live in bubble-surrounded suburbs. The government is no longer willing to pay for public education, so corporations do it instead, raising children to point and buy since birth, and babies themselves are manufactured in hygienic conceptionariums in front of their parents, because having birth "freestyle" isn't doable anymore because the effect of all the ambient radiation.

Wait, what?

Here's the thing: the book isn't about them realizing the errors of their way of life, then rebelling and overthrowing the damaging American corporation-based government, like most contemporary YA would see them do. It's them learning to live and attempt to move on after being forcibly separated with the tech they depend on for not only entertainment, but commerce, news, and essentially, life capital.

This division - particularly for our narrator, Titus, and the odd-girl-out Violet - forces them to confront the shallowness of the world they live in, but not necessarily in a way that prompts them to reject it. This event is a disruption in a seemingly idyllic life, that serves as a sledgehammer to the narrow screens of filtration that keep all the strange and uncomfortable parts of that life out.

It especially throws into sharp relief the lengths people will go to, to distract themselves when the situation gets too horrifying and dangerous to ignore. Instead of fighting back and rallying against the destruction around them, Titus and his friends are content to spend their time analyzing reality television, buying into the newest trends, and moving on from the uncomfortable memories of their attack. While Violet is growing increasingly more aware of the troubles they face - like the lesions sprouting out across everyone's skin for no reason - Titus' parents reward him for his bravery in overcoming the lunar incident by buying him a new car.

Despite the ambivalence of the teenagers, the book isn't anti-Millenial, either. The world isn't dying from Instagram overload; the problems they face are due to previously existing constructs, like a failing governmental system that doesn't take accountability, over-integration of corporate interests into the lifestyles of the general public - especially in areas like Education and Healthcare - and a widening disregard for our relationships with not just foreign interests, but our own low-income populations, as well.

(Hmm... this dystopian world is starting to sound a little familiar.)

This division - particularly for our narrator, Titus, and the odd-girl-out Violet - forces them to confront the shallowness of the world they live in, but not necessarily in a way that prompts them to reject it. This event is a disruption in a seemingly idyllic life, that serves as a sledgehammer to the narrow screens of filtration that keep all the strange and uncomfortable parts of that life out.

It especially throws into sharp relief the lengths people will go to, to distract themselves when the situation gets too horrifying and dangerous to ignore. Instead of fighting back and rallying against the destruction around them, Titus and his friends are content to spend their time analyzing reality television, buying into the newest trends, and moving on from the uncomfortable memories of their attack. While Violet is growing increasingly more aware of the troubles they face - like the lesions sprouting out across everyone's skin for no reason - Titus' parents reward him for his bravery in overcoming the lunar incident by buying him a new car.

Despite the ambivalence of the teenagers, the book isn't anti-Millenial, either. The world isn't dying from Instagram overload; the problems they face are due to previously existing constructs, like a failing governmental system that doesn't take accountability, over-integration of corporate interests into the lifestyles of the general public - especially in areas like Education and Healthcare - and a widening disregard for our relationships with not just foreign interests, but our own low-income populations, as well.

(Hmm... this dystopian world is starting to sound a little familiar.)

I'm almost glad that the book is more focused on the world around them than the teens themselves, because the world-building in this novel is truly the exceptional part. The feed is an extension of your brain, and instead of taking drugs, you download malware - for a price - from European entities to short you out, instead. As you walk through the mall, you are bombarded with advertisements and alluring promises of coolness from each of the stores you walk past. Entertainment has degenerated into familiar plot structures with more and more outlandish elements that get rotated out, alongside their overused, simplistic dialogue and characters. Press is virtually nonexistent, and the only stories anyone knows how to tell are "a sentence long."

My personal favorite image - and one that has stuck with me since finishing the book about two weeks ago - was the idea of factory farms growing to the extreme: instead of mass manufacturing cows for beef, they cut out the middleman - middlecow? - and manufacture tissue instead, directly across mile-long fields of sanitized, plastic-wrapped farmland. Terrifyingly, errors in the genetic coding used to clone this tissue show up in the form of eyes, bones, and even hearts, generated across the clear expanses of living muscle.

In fact, the world was such a vividly-drawn and startlingly realistic one, that I wanted to include lots of quotes for verification, but would have put half the book in one blog post. For instance, in one section, Andersen describes the ways how the corporate interests integrated into the feed work, narrowing social experience to a small segment of identifiable and replicable viewpoints, dictating the whole national culture, that so completely encompassed the ways social media ad algorithms work on Facebook, that I had to put the book down and walk away.

In some cases, the cultural connections are so completely on target, that the black humor is somehow tinged even darker. For instance, one day, Titus and Violet arrive to meet their friends, when they see them all covered in bloody, torn clothing. As they express their distress, their group laughs at their surprise: "Riot Gear" is the newest, hottest trend! I mean, it's all over the feed. One girl, Quendy, even happily models her new clogs, dubbed the "Stonewall" style, but expresses disappointment in their fit: these women's shoes seem to be sized for men.

Once I read that section, I think my eyebrows climbed all the way up into my hairline. It's a bold joke to make. However, it also draws a startling comparison to the Urban Outfitters scandal of Fall 2014, when the trendy retailer's catalog offered a hole-ridden Kent State sweatshirt, covered in daubs of red fabric dye that gave the appearance of sprays of blood. The "vintage"-style $129 sweatshirt was deemed too uncomfortably reminiscent of the 1970 Kent State Massacre, and was ultimately pulled from stores. (Soon after, it gained a lowbrow collector's status on websites like eBay.)

All of these somewhat uncomfortably realistic portrayals of culture, corporate interests, and the American way of life, give greater context to my favorite part of discovering this novel: I was right about its 2000-era status. In fact, this book - with its expert portrayals of social media, personal tech, ad algorithms, and strangely familiar idea of what the end of the world looks like - was written almost 15 years ago, in 2002.

Final Verdict: This book instilled in me the kind of sci-fi nerd love I haven't felt since I read Rodman Philbrick's The Last Book in the Universe for the first time in middle school. It's early-2000s status only amplifies its dystopian message, and it's connections to contemporary culture make it enthralling. I get the feeling that it's a great time to be consuming apocalyptic science fiction.

In some cases, the cultural connections are so completely on target, that the black humor is somehow tinged even darker. For instance, one day, Titus and Violet arrive to meet their friends, when they see them all covered in bloody, torn clothing. As they express their distress, their group laughs at their surprise: "Riot Gear" is the newest, hottest trend! I mean, it's all over the feed. One girl, Quendy, even happily models her new clogs, dubbed the "Stonewall" style, but expresses disappointment in their fit: these women's shoes seem to be sized for men.

Once I read that section, I think my eyebrows climbed all the way up into my hairline. It's a bold joke to make. However, it also draws a startling comparison to the Urban Outfitters scandal of Fall 2014, when the trendy retailer's catalog offered a hole-ridden Kent State sweatshirt, covered in daubs of red fabric dye that gave the appearance of sprays of blood. The "vintage"-style $129 sweatshirt was deemed too uncomfortably reminiscent of the 1970 Kent State Massacre, and was ultimately pulled from stores. (Soon after, it gained a lowbrow collector's status on websites like eBay.)

All of these somewhat uncomfortably realistic portrayals of culture, corporate interests, and the American way of life, give greater context to my favorite part of discovering this novel: I was right about its 2000-era status. In fact, this book - with its expert portrayals of social media, personal tech, ad algorithms, and strangely familiar idea of what the end of the world looks like - was written almost 15 years ago, in 2002.

Final Verdict: This book instilled in me the kind of sci-fi nerd love I haven't felt since I read Rodman Philbrick's The Last Book in the Universe for the first time in middle school. It's early-2000s status only amplifies its dystopian message, and it's connections to contemporary culture make it enthralling. I get the feeling that it's a great time to be consuming apocalyptic science fiction.

What's your favorite dystopian science fiction pick? Would you ever read a book like Feed... or would you prefer to stick to the nightly news, instead? Let me know, in the comments below!

No comments:

Post a Comment